The string of essays I’ve written so far for this newsletter have been a bummer, so I thought I’d take a different tact this week and write about my favorite films of 2024. As much as I spend too much time thinking about politics, the majority of my weeks are honestly more devoted to film. I spend all day at work thinking about acting and scripts, most of my free time is spent with my wife at the movies, the art of filmmaking is at the front of my mind all day every day, and I wouldn’t have it any other way. I saw 60 movies that were released this year and I loved many of them very much! All five of these come with my complete endorsement as films that I think will enrich your life and bring you a lot of joy.

Challengers

There were a surprising amount of great films this year that felt sexy. There were also a lot of films that dealt with sex and our bodies in ways that felt refreshingly frank and honest. Challengers was one of my very favorites that dealt with both: The story of two elite tennis players, Art and Patrick, who were best friends as teenagers at a tennis academy, only to have a bitter falling out over their mutual crush, Tashi, a rising tennis prodigy whose career is cut short by devastating injury. As adults, Art and Patrick meet for the first time in their professional careers at a backwater tennis tournament in New Rochelle, New York, where all their old resentments finally boil over in an explosive match. It’s a tale of lust and attraction, and Luca Guadagnino does a remarkable job linking the libidinal urges of his three leads to their desires to be great athletes. Their sexual bonds to each other are bound up in their bonds on the tennis court; Guadagnino manages to make the tennis matches surge with electric chemistry.

A combination of a top-tier score by Atticus Ross and Trent Reznor (their best since The Social Network) and a fluid use of old-school Italian cameras from the ‘70s in conjunction with cutting-edge CGI makes Challengers easily one of the most technically impressive films from this year. (A TikTok acquaintance made this excellent breakdown of the CG effects in Challengers: It’s a beautiful, seamless use of CG that shows how remarkable these tools can be in the right hands.) The final tennis match at the crescendo of the film is just pure, propulsive magic; we literally spin inside the tennis ball as it ricochets between Art and Patrick, it feels as though we’re a disembodied spirit hurtling between two souls locked in a battle of passion. The cast, with Mike Faist playing Art, Josh O’Connor playing Patrick, and Zendaya playing Tashi, all prove themselves to be the next generation of Hollywood stars. Zendaya, in particular, so clearly dominates every moment she’s on screen; she knows just how to tilt her head so that her furrowed brow conveys intense concentration, there’s a depth behind her eyes where you can feel her calculating and riding a wave of intense emotions at every turn.

I think what’s made the film stick with me for months is how clearly it is a story of people struggling to discipline their bodies to perform at an elite level. Tashi is a tennis prodigy, but no amount of talent and willpower can overcome a brutal knee injury she never recovers from. Art is the least innately gifted of the three, but after he marries Tashi and she becomes his coach, she makes him her surrogate and pushes him into the upper echelons of tennis fame. Patrick, by contrast, may be more innately talented, but without someone like Tashi to push him, he barely scrapes by as a semi-pro. There’s a remarkable moment at the start of the film where we’re shown just how much Art’s body doesn’t belong to him: What he eats, how he exercises, and the clothes he wears are all dictated by his identity as a champion tennis player. This alienation from his own body creates an ennui and unwillingness to truly push himself to be the great player Tashi believes he could be. Meanwhile, Patrick is shown living out of his car and eating and dressing like trash, but even so he’s able to perform as an even match against Art; there’s a sense that he’s much freer, even if he never achieved Art’s greatness.

I got obsessed with bodily alienation and labor this year, as we’ll see in most of the rest of the movies I adored from 2024.

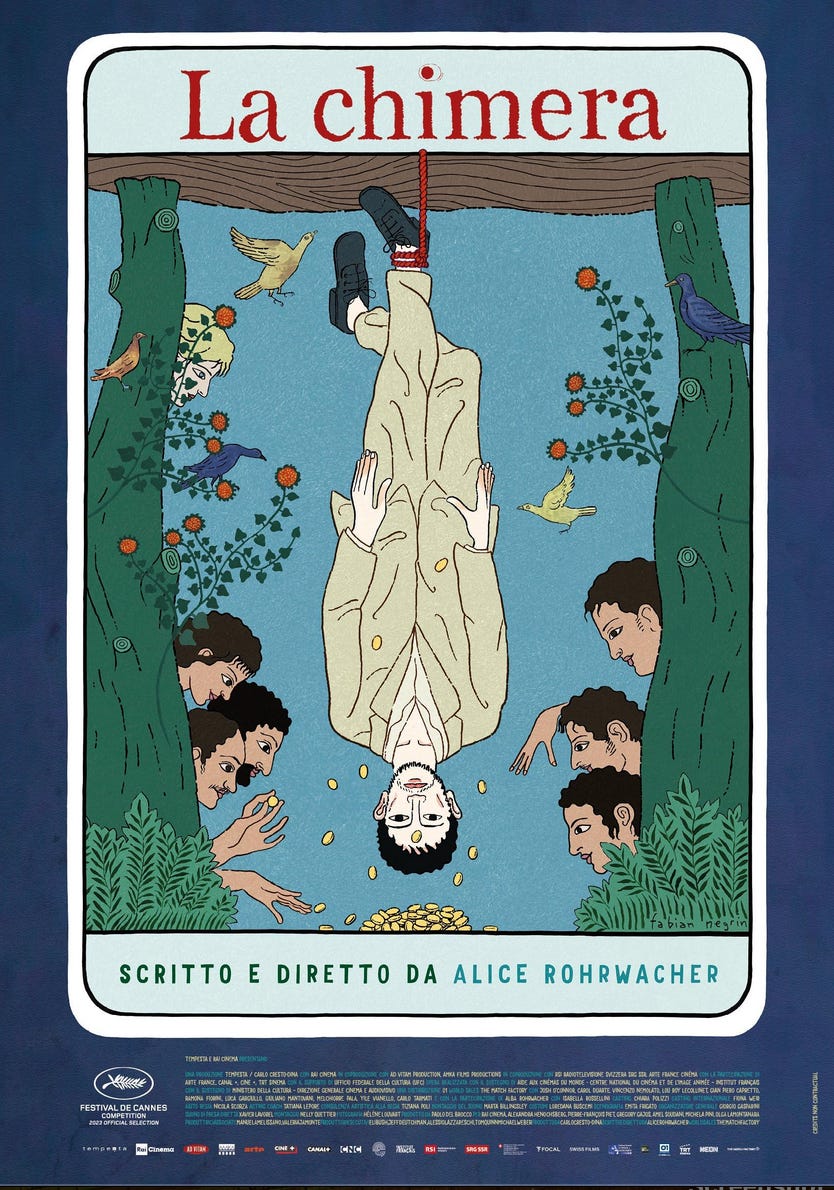

La Chimera

What if you had a supernatural ability to communicate with the ancients, but you couldn’t use it to reach the love of your life after she passed away? That’s the central conceit of Alice Rohrwacher’s excellent La Chimera, a sprawling, philosophically dense, and lyrically rich Italian film. It stars Josh O’Connor, who gives an even better performance here than he did in Challengers. He plays an English archeologist named Arthur who’s really more of a begrudging mystic; with the help of a drunken band of Italian misfits, he can use a dowsing rod to uncover ancient Etruscan tombs in the Italian countryside and loot them to sell their treasures. He’s grieving the death of his girlfriend and eventually connects with her mother, Flora (played by a restrained but lovely Isabelle Rosellini), in her dilapidated mansion. Complex conversations about history, memory, art, and the ownership of property ensue.

And yet, despite the heaviness of the subject matter, La Chimera has this remarkable dreamlike quality. (In Italian the title literally means “The Impossible Dream.”) The film opens on Arthur waking from a nap on a train: I’ve never seen a more vivid depiction of what it feels like to flicker between dreaming and waking life. There’s a humor and breathlessness to most of the film even though Arthur is clearly burdened by loss. Over time, you come to realize the film is interested in the meaning of property rights. The question of whether or not the graverobbers have the right to steal from the long-dead leads to a question over whether the wealthy have a right to hoard the artifacts they plunder. Arthur starts the film squatting in a rustic shack, hurting no one but also not paying rent, until he’s eventually evicted from it. The run-down mansion Isabella Rosellini inhabits is eventually overtaken and turned into a women’s commune. All these interesting challenges to the logic of capitalism are raised, but in a way that feels entirely organic and observational, like Rohrwacher is an alien studying human behavior in all its beauty and contradictions. The ending may be crushing, but the film vibrates with such an wonderous intensity that it’s stayed with me for a full year, despite only seeing it once.

This review of the film by Fran Hoepfner in Bright Wall/Dark Room is the best piece of film criticism I read this year.

Anora

Questions of bodily autonomy and alienation from your labor abound once again in Sean Baker’s Palme D’or-winning Anora. It tells the Cinderella story of a New York stripper/escort named Anora or “Annie” (played like a mouthy Barbara Streisand by the immensely gifted Mikey Madison), who enchants the young son of a Russian oligarch into marrying her. The marriage only lasts a few days before the oligarch gets wind of the marriage and forces an annulment. It becomes a story of the fantasy created by obscene wealth, and how easy it is for anyone to fall for it.

Sean Baker is my favorite American filmmaker working today. He has chosen sex workers as his subjects of his films since 2015’s Tangerine, and he tells their stories with an aching honesty and compassion. Rather than spinning tales of tragic figures exploited and abused by everyone around them, Baker tells stories of people living at the margins and fighting for their survival and dignity. He manages to portray sex work with blunt clarity while also demonstrating why it’s a line of work that people from many different backgrounds find appealing. His films serve as remarkable portraits for understanding the complexities of people’s attitudes around money, sex, poverty, and fairness. The characters his sex workers encounter reflect a tapestry of many different Americas contesting for legitimacy on the periphery. Tangerine tells the story of two Black, trans sex workers in Hollywood; despite being only blocks from the glamor and gentrification, they live for day-by-day survival with grit, humor, and tenacity. Florida Project is the story of a young sex worker providing for her daughter in a motel in Orlando just outside of Disney World. Anora is by far the biggest and most glamorous film Baker has made to date; Annie travels to Vegas and parties in a mansion before the world comes crashing down on her.

Baker understands that sex work is work. He gets that it’s a vulnerable and precarious job, but that it’s an extension of the preacrity we all deal with in some capacity. The tragedy of Anora is how much Annie lets herself get caught up in the fantasy she is selling. I think this is where the universal themes enter the film; most of us will never know what it’s like to be a high-end stripper, but we all know what it feels like to buy into the fantasy that one day we might get lucky and strike it rich. Annie truly believes that she’s hit the jackpot, and it takes her a devastatingly long time to admit that her golden ticket has slipped through her fingers. Even as she’s forced to accept that the ride is over, she’s forced to negotiate for what she’s owed, and her savvy and cunning is instantly relatable to anyone who’s had to fight a shitty boss to get paid. The American story might most purely be understood to be the belief that we’re one lucky streak away from becoming millionaires, and we let our hearts get broken every time it fails to become true.

Many people making films like this would choose to make them straight dramas, but Baker has always leaned into humor to ground his films, and Anora has moments that are uproariously funny. Despite how dire Annie’s circumstances become, she moves with a defiant confidence that leaves you doubled over laughing where things could easily be terrifying. The high-wire act between comedy and tragedy is something that makes Baker an incredible storyteller; he knows how to play in different keys to give you the full spectrum of human emotions before he crushes you at the end. There are people online who’ve accused Baker of being a closet conservative, he’s expressed support for Tulsi Gabbard and was following the infamous Libs of TikTok account at one point, but I see him as more of a political independent frustrated with both parties, as most Americans are these days. He is clearly a firm believer that all workers deserve dignity, and someone who believes in championing the stories of people who are normally kept from the spotlight. I can’t wait to see what he does next.

The Substance

No matter how highfalutin I might seem in my film opinions, I’m a horror junkie at the end of the day. The Substance would have probably been one of my favorite films from this year purely based on its disgusting body horror effects that are a loving tribute to the practical effects wizard Screaming Mad George. The film is the story of a Hollywood starlet, Elisabeth, who turns 50 and is summarily ejected from her sexy aerobics show. Scorned by the rejection (and the loss of her income), she enrolls in a secretive program in which she injects herself with a mysterious serum that replicates her cells to create a younger, hotter version of herself. She is comatose for a week while her younger self, named Sue, moves about the world, and then Sue has to be comatose for a week while Elisabeth lives.

The film is ruthlessly well-designed. The packaging of the titular substance is alluring and hyper-modern: It looks like an elite subscription box the Kardashians might advertise on their Instagram. The feel of Elisabeth’s luxurious penthouse apartment overlooking the LA skyline is intoxicating; you can instantly understand why she refuses to give it up, even as the apartment steadily becomes her prison. The score is a punishing, bass-heavy techno, reminiscent of elite runways and exclusive nightclubs, but pulsing with a menace that constantly ups the stakes. There’s a constant sense of loneliness and anxiety simmering through the whole film, but also an addictive compulsion to keep moving, to keep the machine running and never stop no matter the consequences.

Even as the process of cell transformation is shown to be horrifying (Elisabeth’s whole body has to split in two to birth Sue), Elisabeth is also clearly entranced to see her ideal Pygmalion form. Sue immediately gains fame on an even more pornographic version of Elisabeth’s aerobics program; director Coralie Fargeat manages to make Sue’s workout videos nauseating as she twerks in 8K under incandescent studio lights. Some people were thrown by the anachronistic feel of the movie; it seems both trapped in an ‘80s version of Hollywood and thoroughly fixed in the Instagram age. But I see the parallel as very intentional; Elisabeth may be of one generation and Sue the next, the technology may have changed, but the conditions of hyper-commodification and objectification remain the same. The men in the film are uniformly portrayed as leering hyenas or perverted buffoons, which some people found reductive, but to that I say, have you met men in LA?

I’ve read a lot of well-considered criticism that sees the film’s feminist politics as too shallow or even contradicted by how mean-spirited the film can seem towards Elisabeth. I think it’s totally fair if that’s your interpretation, but I saw the film as being very profoundly about the commodification of the body. Elisabeth feels she has to undertake this radical treatment in order to still have value in society; her job is literally her image, and if the attention economy no longer wants her, she has to meet the demands of the market. The film gets really interesting when her clone begins to ignore Elisabeth’s wishes and keeps her in the coma for longer and longer. She literally becomes alienated from her own body, in many ways because she is intoxicated by the wealth and fame afforded to her younger self. She knows subconsciously that this will be devastating for her in the long term, but she can’t face the threat to her life when she is so swept up in keeping the machine purring. The film becomes an examination of how we are conditioned to believe that we are one health hack away from staying beautiful and living forever.

Also, it’s just really gross and keeps you in a perpetual state of whiplash between laughter and terror! It’s truly one of the most unique and extreme horror films I’ve ever seen.

Nosferatu

All the films on this list are ones that I’d place in my personal canon of favorite films, but Nosferatu is the one film that I believe will ultimately end up in The Canon. Robert Eggers’ command over his camera, the precise way he stages his scenes, is on a level most of his contemporaries can’t touch. Eggers read about 400 books on the period the film takes place in, and his heads of department share his obsession with historical accuracy. What makes him such a remarkable filmmaker, however, is his ability to find the complexity and wildly contradictory beliefs and attitudes of people living at the same time; there is no uniformly agreed-upon reality that all the characters inhabit from one moment to the next. Nosferatu is about the transition towards capitalist industrialization and the aftereffects of the Enlightenment, and a reminder that it came at a tremendous cost. It’s also about the restrictions and oppression placed on women during the Victorian period, and how those conditions ripple out to today.

The film is a faithful retelling of F.W. Murnau’s iconic silent film, which essentially popularized horror as a genre and introduced vampires to cinema. Nosferatu tells the story of Ellen Hutter, a young woman who has just married a real estate solicitor, who is troubled by dark dreams and fits of hysteria. When Ellen was young, she cried out to any spirit who could save her, and a demon known as Nosferatu answered her call and possessed her. Despite loving her husband, she is bound to serve the will of this demon, who has taken on the body of a Transylvanian nobleman known as Count Orlock. This tension, between Ellen’s desire to protect her husband and her inability to overcome the darkness that pulls at her soul, becomes the central tension of the film. Where Eggers’ diverts from Murnau’s original is in making Ellen the central protagonist of the film, rather than a tragic, helpless maiden sacrificed in the final moments of the film.

Ellen, embodied by a truly inspired Lily Rose-Depp, struggles mightily to make anyone else understand the threat and the terror that she knows is hurtling towards them. As Count Orlock comes closer and closer to ravaging the Germanic city she lives in, Ellen becomes consumed with night terrors, and the wealthy family taking care of her only knows how to treat her with restraints, corsets, and ether. It’s only when they consult a mad doctor, von Franz (played by a delightfully demented Willem Dafoe), that they start to unlock the mystery of what is happening to Ellen. Von Franz is a trained medical doctor, but he has become obsessed with the occult and arcane spiritual technologies. Again and again throughout the film, Eggers underlines how the transition to modernity and the scientific method actually leave the subjects of his film vulnerable to ancient forms of evil. Even more importantly, the insistence on maintaining the strict gender roles of the time period means Ellen is dismissed and ignored until it is too late. As von Franz tells her, “In a different age, you would have been a great priestess of Isis”.

Part of why I love Nosferatu so much is that it reminds me so much of Silvia Federici’s incredible book Caliban and the Witch. That book tells the story of the development of modern patriarchy in Europe through the lens of the enclosure of the commons and the transition to capitalist production. She demonstrates in that book that the femicide of women that took place in the form of witch burnings wasn't a simple Christian superstition run amok, but a disciplining of women who had practiced forms of healing and held privileged positions in society into accepting their place in subordination to men. She demonstrates how violence against women was systematically endorsed as a way to claim their sexual reproduction as the property of men. By 1838, Ellen desperately wants to fit into the confines of patriarchy; she wants to be a good, normal wife, but she is incapable of it. Just like in Eggers’ first film The Witch, the story is about a young woman transcending the strict boundaries imposed on her by men, even if it comes at a terrible cost.

I plan on writing a much longer essay about the film in this newsletter later this year, so I’ll leave it there for now. Please go see this film in theaters if you are able, it is truly a singular experience. I saw it in a packed theater and the entire audience was enraptured. It’s beautiful, it’s heartbreaking, and it’s terrifying. You will not have another experience like it in a movie theater for a very long time.